Sunoco LP (SUN) | World Kinect Corporation (WKC) | Global Partners LP (GLP) | CrossAmerica Partners LP (CAPL) | ARKO Corp (ARKO)

The fuel distribution and marketing industry is part of the downstream segment of the oil & gas value chain. After crude oil is extracted (upstream) and refined into fuels like gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, etc., those refined products must be transported, distributed, and sold to end-users. Fuel distributors and marketers handle this critical “last mile” of the petroleum supply chain, bridging refineries (or bulk terminals) and consumers. They operate extensive logistics networks – including pipelines, storage terminals, truck fleets, and retail fuel stations – to deliver refined fuels to gas stations, trucking fleets, airports (for aviation fuel), marinas (for marine fuel), industrial customers, and even heating oil consumers.

Position in the Value Chain: Fuel distribution & marketing is the final link in the petroleum value chain. It is considered “downstream” – after refining – and encompasses all activities required to get finished fuels to end customers. Many large integrated oil companies (ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP, etc.) have downstream divisions that include refining and marketing. However, the U.S. also has independent fuel distributors/marketers whose core business is moving and selling fuel rather than refining it. These companies often purchase fuels from refiners or in bulk markets, then transport, store, and resell them via wholesale channels (to fuel retailers or commercial accounts) or directly to consumers (through company-operated gas stations or delivery services). Some independents focus on specific niches (e.g. supplying jet fuel to airlines, marine bunker fuel to ships, or unbranded gasoline to independent stations), while others operate broad multi-fuel distribution businesses.

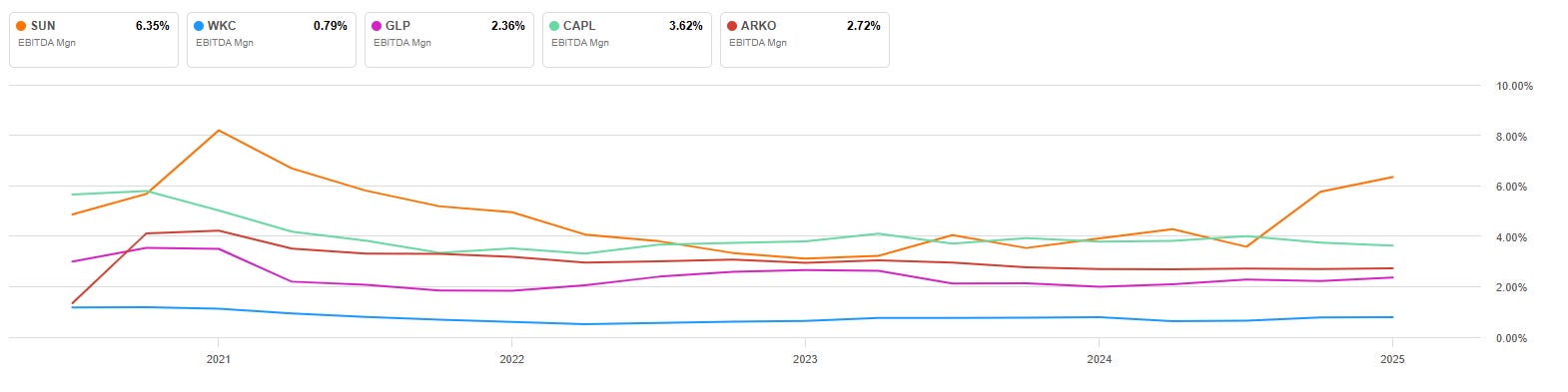

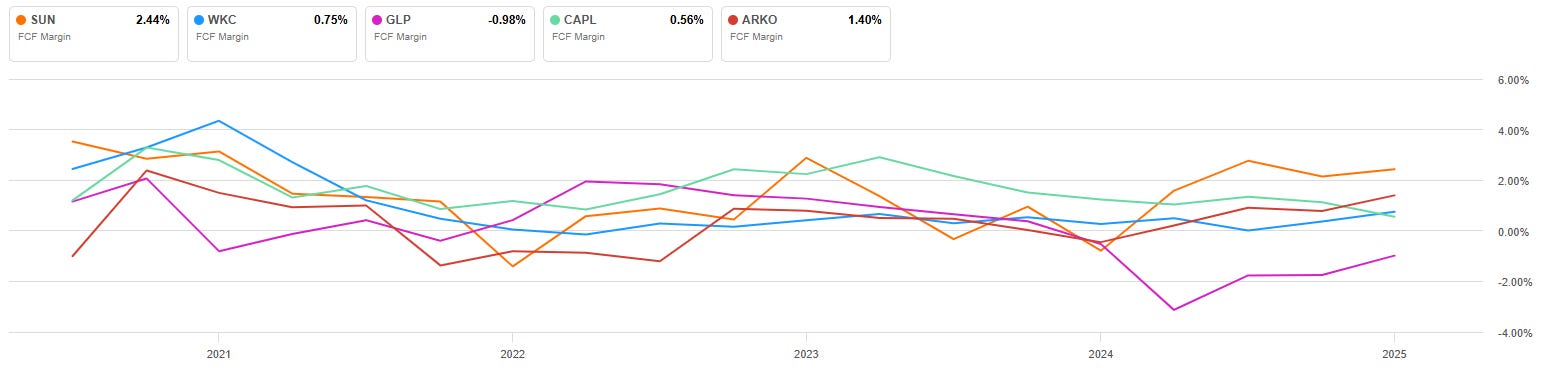

Industry outputs are fuel supply availability, logistics efficiency, and retailing of fuel. Fuel distributors earn margins per gallon (often only a few cents) for moving product through their networks, and fuel marketers at retail earn a markup on fuel sales (also quoted in cents per gallon) and often earn additional gross profit from convenience merchandise, services, and food sales at gas stations. It’s a high-volume, low-margin business that relies on operational scale, supply chain optimization, and effective pricing/marketing strategies to be profitable.

🏭 Key Companies

Sunoco LP (SUN)

Overview & Positioning: Sunoco LP is one of the largest independent fuel distributors in North America. It is a master limited partnership (MLP) that operates across 47 U.S. states (and also has assets in Puerto Rico, Canada/Europe, and Mexico after recent expansions). Sunoco delivers approximately 9 billion gallons of motor fuel annually, making it the nation’s largest independent fuel distributor by volume. A unique aspect of Sunoco is that it is the only independent fuel distributor with a major national fuel brand – the Sunoco brand, which has over 100 years of history.

Sunoco’s business today is focused on wholesale fuel distribution, in contrast to a few years ago when it also operated many retail gas stations. In 2018, Sunoco LP divested the bulk of its company-operated convenience stores to 7-Eleven, and instead signed a long-term agreement to be 7-Eleven’s fuel supplier. This shifted Sunoco’s strategy to an “asset-light” wholesale model where it supplies fuel to approximately 10,000 locations (gas stations, dealers, commercial and industrial fuel customers) while owning far fewer retail outlets itself. Sunoco’s general partner is owned by Energy Transfer (ET), a large midstream pipeline company, which provides strategic support.

Pricing Model: Sunoco typically earns a fixed fuel margin per gallon under many of its supply contracts. For example, its cornerstone contract is with 7-Eleven (supplying the former Sunoco convenience stores that 7-Eleven acquired) – this contract “ensures a fixed price” for Sunoco, effectively guaranteeing a fixed cents-per-gallon margin on those volumes. Many of Sunoco’s other distributor and dealer supply agreements similarly use a formula pricing where Sunoco’s selling price is based on a wholesale benchmark plus a fixed markup. This model makes Sunoco’s gross profit per gallon relatively stable, insulating it from day-to-day commodity price swings. Sunoco leverages its scale to buy fuel at competitive rates (including bulk purchases direct from refiners and utilization of its own terminals) and then locks in margin on resale.

Because Sunoco owns a nationally recognized brand, it can sign dealers to exclusive long-term contracts (often 7 to 10 year supply agreements) which lock in those stations to buying Sunoco-branded fuel. Branded fuel typically allows a higher margin than unbranded since consumers recognize and trust the brand. Sunoco also distributes unbranded fuel to independent stations, but having the Sunoco brand network is a competitive advantage in expanding margin opportunities.

Recent Strategic Initiatives: Sunoco has been pursuing growth via acquisitions and diversification within its core domain. Its headline move was the acquisition of NuStar Energy L.P. in 2024, a transformative deal that greatly expanded Sunoco’s midstream infrastructure. NuStar was an MLP owning pipelines and fuel terminals; Sunoco acquired the entire company in an all-equity ~$7.3 billion transaction (closed May 2024). This added approximately 9,500 miles of pipelines and over 100 fuel terminals to Sunoco’s asset base, more than doubling Sunoco’s storage capacity and extending its geographic reach. Importantly, a major portion of NuStar’s business was fee-based pipeline and terminalling services (with long-term contracts), which adds stable, utility-like cash flows to Sunoco’s portfolio.

Aside from NuStar, Sunoco has been expanding its fuel distribution business into new sectors and regions. It has a growing presence in transmix processing (reclaiming usable fuel from mixed fuel waste) and in fuel distribution in Hawaii and Puerto Rico (via earlier acquisitions of midstream and retail assets in those markets). The partnership is also exploring emerging fuel opportunities: it markets ethanol and biofuels through its terminals, and its scale gives it the flexibility to blend products or move fuel cargoes where demand is highest.

World Kinect Corporation (WKC)

Overview & Positioning: World Kinect Corporation – until mid-2023 known as World Fuel Services (INT) – is a global fuel distribution and energy management company. Headquartered in Miami, WKC is quite different from the others in that it primarily serves commercial, industrial, and government customers worldwide, rather than operating retail gas stations. It has three main segments: Aviation, Marine, and Land. In aviation, WKC is a major supplier of jet fuel to airlines, airports, and private aviation – it handles fueling operations or fuel contracts at hundreds of airports. In marine, it supplies fuel (bunker fuel, marine diesel) to shipping fleets and vessels at ports around the globe. The land segment is more diverse: it includes distribution of gasoline, diesel, propane, and lubricants to commercial fleets, industrial sites, heating oil customers, as well as wholesale fuel supply to independent gas stations and truck stops. Additionally, World Kinect has expanded into natural gas and electricity retailing in certain markets, and offers a suite of sustainability and energy management services (like carbon offset programs, renewable energy procurement, and energy data management).

It does not own refineries; it typically purchases fuel from producers or in bulk markets and resells/delivers it to end-users, often coordinating complex logistics. Nor does WKC own a large chain of gas stations – instead it might supply independent station owners (and offer them branding solutions), or manage fuel procurement for corporate fleets, etc. This asset-light, service-heavy model means WKC’s revenues are huge (tens of billions of dollars) but its profit margins are very thin (since it’s mostly pass-through fuel cost plus a small markup). The company’s strategy is to improve profitability through value-added services and expanding into higher-margin energy segments.

Pricing Model: World Kinect historically operated on a fuel distribution margin model – buying fuels at one price and selling at a slightly higher price, pocketing the difference. Given the commodity nature, the gross margin per gallon or per metric ton is typically very low. For example, in 2024 WKC’s average gross margins were reported as ~2.11¢ per gallon in the land segment and ~2.62¢ per gallon in aviation, and about $536 per metric ton in marine. These margins actually declined from 2023 (2024 margins were ~12% lower in aviation and land), illustrating the volatility and competitive pressure in their markets. WKC often enters into contracts with customers where pricing can be tied to market indices plus a fee, or it may act as a broker/agent earning a commission for arranging fuel supply. In some cases (especially aviation fuel supply to airlines), WKC might take title to fuel and bear inventory risk; in others it’s simply facilitating a sale between a refinery and an end-user for a fee.

To improve margins, World Kinect has been shifting toward more complex service offerings. It provides price risk management for clients (fuel hedging, etc.), fuel quality control, logistics management, and even advisory on sustainability (helping customers transition to lower-carbon energy). These services can command fees beyond just the fuel markup. The company also now supplies renewable fuels (like sustainable aviation fuel, biodiesel, renewable diesel) where available, and offers energy procurement for electricity and natural gas in deregulated markets, essentially acting as an energy retailer. These newer products often carry higher unit margins or at least diversify the revenue stream.

Another aspect of WKC’s model is efficiency and scale: it operates in over 200 countries/territories and leverages centralized systems to manage fuel transactions. Its scale allows for negotiating favorable supply contracts with refiners and suppliers worldwide. It also manages credit risk and financing for customers – e.g. extending credit to airlines for fuel purchases – effectively earning a financing margin too. Nonetheless, the industry is competitive, so WKC’s strategic emphasis is on driving operational efficiency and expanding into higher-value offerings rather than simply growing fuel volume.

Recent Strategic Initiatives: In the last few years, World Kinect has undergone a strategic pivot toward sustainability and diversified energy solutions. The rebranding in 2023 was part of this effort – the new name “World Kinect” reflects an emphasis on “connecting” customers with not just fuel, but a range of energy needs including renewables and data-driven services. Concretely, WKC has made acquisitions and investments in the sustainability space: for instance, it had earlier acquired a company that specializes in sustainability consulting and energy management (World Kinect Energy Services, formerly Kinect Energy Group), which gives it capabilities in advising clients on carbon footprint reduction, renewable energy procurement (like facilitating corporate purchase of wind/solar power or renewable energy certificates), and carbon offset programs. The company has also been active in supplying Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) to airline customers in limited quantities and blending biofuels for land transport clients as regulations demand.

Global Partners LP (GLP)

Overview & Positioning: Global Partners is a vertically-integrated downstream energy company headquartered in Massachusetts, structured as an MLP. It has a strong presence in the U.S. Northeast and expanding operations in other regions. GLP’s business spans wholesale fuel distribution, fuel terminals, and retail gas stations/convenience stores.

Historically, GLP started as a heating oil and gasoline distributor in New England, and over the years it has acquired a network of terminals and storage tanks as well as a portfolio of gas stations and convenience store brands. Today, Global handles a variety of products: gasoline, distillates (diesel and heating oil), kerosene, ethanol and other biofuels, and even crude oil trading in some instances. It operates roughly 49 refined product terminals across the East Coast, Southeast, and Texas (this figure jumped after a recent acquisition – see below). On the retail side, GLP either owns, leases, or supplies around 1,700 gas stations in 33 states, of which a few hundred are company-operated convenience stores and others are dealer-operated sites under fuel supply contracts. GLP’s retail brands include convenience store banners like Alltown, XtraMart, Honey Farms, and Jiffy Mart, and it is also a distributor for major fuel brands (Exxon, Mobil, Shell, Sunoco, Gulf, etc.) at many stations. Its station operations also generate rental income where it leases sites to other operators.

Strategically, Global Partners positions itself as a “one-stop downstream fuel provider” – it owns upstream logistics (terminal storage, pipelines), midstream transport assets (it has some barges and rail transloading for moving crude and ethanol), and downstream marketing assets (gas stations and supply contracts). This integration can provide profit at multiple steps: bulk storage and terminalling fees, wholesale distribution margin, and retail margin. The company’s Gasoline Distribution and Station Operations segment (GDSO) has been a focus for growth, as it provides higher margins (retail and convenience store sales) and direct access to end consumers. GLP’s Wholesale segment deals with bulk fuel sales and logistics, which has lower per-unit margin but high volume and can capitalize on market volatility (for example, Global is known to take advantage of arbitrage opportunities in storing or blending fuels).

Pricing Model: Global Partners’ pricing and margin model is mixed, reflecting its integrated segments:

In Wholesale, GLP buys refined products from refiners or in spot markets and sells to wholesale customers (which could be fuel resellers, industrial accounts, or even its own retail network). Margins here are typically a few cents per gallon or per barrel. Global sometimes benefits from blending (e.g., mixing butane or ethanol into gasoline to capture extra margin) and from storage arbitrage (buying and storing product when prices are low and selling when higher).

In GDSO (retail), Global earns the retail fuel margin (difference between wholesale cost and pump price) as well as merchandise margin in convenience stores and rental income from leased sites. Retail fuel margins are higher (in cents/gallon) than wholesale, but volumes per site are smaller. For example, GLP’s retail segment fuel margin is often around 20–30+ cents per gallon (industry typical for retail), compared to wholesale margin under 10 cents.

Terminalling: With its terminals, GLP earns fees by storing and throughputting third-party volumes (especially now with the Motiva contract, see below). Those fees are often based on capacity reserved (take-or-pay contracts) and are fixed, contributing to stable income.

Recent Strategic Initiatives: Global Partners has been very active in M&A and strategic expansion, calling 2023 a “transformational year”. The most significant initiative was the acquisition of 25 liquid fuel terminals from Motiva Enterprises (Saudi Aramco’s refining arm). This deal closed in late 2023 and “nearly doubled GLP’s storage capacity”, adding terminals along the Atlantic Coast, Southeast U.S., and Texas. Crucially, the transaction came with a 25-year take-or-pay throughput agreement with Motiva – Motiva remains the anchor tenant using those terminals and guarantees minimum annual revenue to GLP for 25 years. This provides extremely stable, long-term cash flows to GLP and effectively means the deal will pay back steadily over time.

Another major move: Retail JV with ExxonMobil – In 2023, GLP formed a joint venture (Spring Partners Retail LLC) with Exxon to acquire 64 convenience stores and gas stations in the Houston, Texas market (from the Landmark group). Global is the managing member and operator of the stores, leveraging its retail expertise, while Exxon likely provides capital and secures fuel supply (presumably these sites carry Exxon/Mobil branding). This was GLP’s first foray into the Texas retail market at scale. It gives Global a platform in a high-growth metro (Houston) and aligns with a supermajor as a partner.

Additionally, GLP had agreed to acquire 5 more refined product terminals from Gulf Oil in the Northeast in 2023. This further strengthens their Northeast logistics presence.

On the divestment/optimization side, GLP has been converting some gas stations from dealer-supplied to company-operated to capture more margin. It mentioned “converting sites to our retail class of trade” as a strategic goal in 2024. Essentially, instead of just leasing a site to a commission agent or dealer for a fixed cut, GLP takes over operations to earn the full retail gross profit.

GLP is also inching into renewable fuels. It has handled ethanol blending for years and, given its terminal network, it can store and distribute biodiesel or renewable diesel. In fact, it opened the first East Coast retail station selling renewable diesel in early 2024 (through an affiliate, likely leveraging its supply connections). With low-carbon fuel standards possibly expanding, GLP’s storage and distribution assets could be used to move greater volumes of renewables. The partnership is also involved in Renewable Natural Gas (RNG) via a small project capturing methane from dairy farms (showing an interest in new energy opportunities, though currently tiny in scope).

CrossAmerica Partners LP (CAPL)

Overview & Positioning: CrossAmerica is a smaller fuel distribution MLP based in Pennsylvania. It primarily operates as a wholesale fuels distributor to gas stations and a lessor of gas station properties, with a growing segment of company-operated convenience stores. CrossAmerica’s roots were as an independent “jobber” (fuel wholesaler) supplying service stations in the Lehigh Valley, PA region (originally known as Lehigh Gas). Over the past decade, through a series of transactions, CAPL’s business became entwined with major convenience retail companies. It was previously affiliated with CST Brands (Valero’s spinoff) and later with Alimentation Couche-Tard (Circle K’s parent), and underwent asset exchanges with those firms.

Today, CrossAmerica supplies fuel to about 1,700 locations across 34 states. These include both dealer-owned stations (where CAPL delivers fuel under supply contracts, often with branding rights) and commission agent or lessee stations (where CAPL owns or leases the site and either operates it via commission agents or leases it out). As of the end of 2023, CAPL also directly operated 295 convenience stores itself – this number has been rising as the partnership acquires or converts more sites to company-operation. CrossAmerica does not own refining or large terminal assets (unlike Sun or GLP); it typically purchases fuel from refiners or the spot market and resells/delivers it via contracted carriers.

CrossAmerica’s competitive strength has been its close relationships with big convenience store operators. In the past, Couche-Tard (Circle K) actually owned CrossAmerica’s general partner and utilized CAPL as a vehicle for distributing fuel to some of Circle K’s stores in the U.S. Although Couche-Tard divested its ownership in CAPL in 2019, the companies have continued strategic transactions. CAPL essentially serves as a specialist in owning or leasing stores and handling fuel supply, while Circle K focuses on retail operations in many cases.

Pricing Model: CrossAmerica’s revenue comes from two main streams: fuel distribution margin and rental/commission income from stations. On fuel sales, CAPL’s wholesale supply agreements typically yield a fixed-cents-per-gallon margin or a percentage margin. As of 2024, CAPL’s wholesale fuel margin was around 8.5¢ per gallon (slightly down from 8.6¢), and its volume was ~0.74 billion wholesale gallons for the year (which actually fell ~12% in 2024). The decline in volume was partly due to strategic shifts – as CAPL converts some supplied sites into company-operated, those gallons move from “wholesale” category to “retail” category in their reporting. Meanwhile, CAPL’s retail fuel margin at its company-operated stores was about 36.8¢ per gallon (essentially flat year-on-year).

Additionally, CAPL earns rental income and commission income. In cases where CAPL owns a station but a third party operates it, CAPL might lease the property to them and collect rent, or supply fuel on a commission basis (where the operator gets a fixed commission and CAPL keeps the remaining margin). These rents/commissions are relatively stable and often indexed to volume or sales. CAPL’s business model thus relies on securing long-term supply contracts and leases that lock in a steady flow of income, while minimizing exposure to commodity price swings (like others, they often pass through wholesale price changes and just keep the per-gallon fee).

Recent Strategic Initiatives: CrossAmerica’s recent moves center on acquisitions (both of stores and fuel supply portfolios) and portfolio optimization. Some key initiatives:

Acquisition of 59 Applegreen Stores (2024): In early 2024, CrossAmerica announced a deal to acquire 59 convenience stores from Applegreen (an Ireland-based company that had U.S. assets) in Florida, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Applegreen had taken over these stores around 2018; CAPL is buying them for $16.9 million – a relatively low price, suggesting perhaps these are gas stations with perhaps franchise agreements or needing some investment. The rationale is to “company-operate these locations” and boost CAPL’s retail segment earnings. This shows CAPL expanding geographically (Florida and the Upper Midwest are new or enhanced territories for them) and growing its base of directly operated sites.

7-Eleven/Speedway Assets: CAPL made a significant acquisition in 2021 – it purchased 106 convenience stores from 7-Eleven. These stores were likely part of the divestitures required when 7-Eleven bought Speedway from Marathon; CrossAmerica was one of the buyers chosen to take over certain locations to satisfy antitrust concerns. This gave CAPL a big influx of stores (in various states) and was transformative, increasing its scale.

Fuel Supply Contracts Acquisition: In late 2022, CAPL acquired certain wholesale fuel supply contracts (and associated assets) from a company called Community Service Stations for $27.5 million. This added volume to its wholesale segment (and presumably new gas station customers). CAPL’s strategy includes quietly executing such “bolt-on” deals for supply agreements, which increase volume without heavy capital (no need to buy real estate, just purchase the supply relationships).

Divestments: CAPL has also been trimming its portfolio of owned properties. In 2022, it sold 27 properties for ~$12.9 million, and in 2023 sold 10 properties for $9.2 million. These were likely smaller or underperforming sites considered “non-core.” Management signaled an intention to “divest more non-core stores in 2024 than in 2023”, indicating a focus on shedding lower ROI assets and focusing on key markets.

CrossAmerica is smaller and more regional than Sunoco or Global. It doesn’t have the scale advantages, so its margins are a bit thinner and it has higher exposure to single markets. Its affiliation with Couche-Tard is now only through ongoing business agreements (Couche-Tard sold its ownership, as noted), but Couche-Tard remains a major customer and there is a lot of intertwining (they even settled an FTC penalty in 2020 for allegedly not fully separating some management between the two during asset exchanges. Investors typically view CAPL as a high-yield, slow-growth entity – it pays a large distribution (~10%+ yield) which attracts income investors, but it must carefully balance that with funding growth.

ARKO Corp. (ARKO)

Overview & Positioning: ARKO Corp is one of the fastest-growing convenience store operators and fuel marketers in the U.S. over the past decade. Based in Richmond, VA, ARKO has built a portfolio of approximately 1,500 company-operated convenience stores and gas stations (as of 2023) across 33 states, making it one of the largest convenience store chains nationally. In addition, through acquisitions, it has a wholesale fuel distribution segment that supplies over 1,800 other sites (some of which carry its brands, others are dealer-owned). ARKO’s stores operate under a “Family of Community Brands” – they intentionally keep local brand names that have regional recognition. These include names like Kenyon’s, Fas Mart, E-Z Mart, Village Pantry, Handy Mart, Admiral, Pride (and numerous others from acquired companies). ARKO’s strategy has been to consolidate the fragmented c-store industry, buying up small to mid-sized chains and integrating them to achieve economies of scale in purchasing, operations, and marketing.

The company’s revenues are primarily from fuel sales (which account for a majority of sales dollars) and secondary from merchandise sales inside stores. Unlike Sunoco or CAPL, ARKO’s focus is strongly on retailing: fuel sales are a means to drive traffic to their convenience stores, where they sell higher-margin items like snacks, beverages, foodservice, and lottery. That said, ARKO also inherited wholesale fuel distribution businesses in some acquisitions, so it does have a wholesale segment now – e.g., it acquired the business of Empire Petroleum’s wholesale arm and Quarles Petroleum’s fleet fueling business, which added hundreds of wholesale fuel accounts and cardlock (commercial fueling) sites.

Strategic Position: ARKO positions itself as a value-added acquirer and operator. Its playbook is to acquire stores (often ones that were a bit neglected under previous ownership or are ripe for improvement), then implement “The ARKO Way” – a set of best practices in merchandising, loyalty programs, category management, fuel pricing, and cost control – to boost profitability at those stores. The company emphasizes growing merchandise sales and margins (where it can differentiate via product mix and pricing) and optimizing fuel gross profit dollars rather than chasing volume.

Pricing Model: ARKO’s revenue streams can be broken into:

Retail Fuel Sales: ARKO sells billions of gallons of fuel through its stores. It earns a margin per gallon that fluctuates with market conditions. In 2022, retail fuel margins hit a record high (over 41 cents per gallon, industry-wide margins spiked due to volatility). In 2023, margins normalized down somewhat – e.g., Q3 2023 retail fuel margin was 40.3¢/gal vs 44.8¢ a year prior. ARKO’s strategy with fuel is often to optimize gross profit dollars rather than volume. This means they may sacrifice a bit of volume if needed to keep margins healthy, especially in times of rising costs.

Merchandise Sales: ARKO generates roughly 30-35% of its gross profit from in-store merchandise (which includes foodservice). Merchandise carries much higher gross margins (over 30%).

Wholesale Fuel Sales: ARKO’s wholesale segment (resulting from acquisitions like Empire, ExpressStop supply, etc.) sells fuel to independent dealers. This operates like a typical jobber – ARKO earns a few cents per gallon on these sales or a commission. For instance, ARKO supplies over 200 ARCO-branded stations on the West Coast (from a deal with BP) and many independent stations in the Southeast from the Empire acquisition. The wholesale segment contributed less to EBITDA than retail, but it adds stable volume and some diversification. Wholesale margins are thinner than retail (often single-digit cents).

ARKO’s overall financial model is growth-oriented: it reinvests a lot into acquisitions and capital projects (like remodeling stores) to drive future profit, rather than paying dividends. The company also uses sale-leaseback financing extensively: after acquiring stores (which often include real estate), ARKO will sell the real estate to a partner (e.g., Oak Street Real Estate) and lease it back, freeing up capital to fund more acquisitions.

Recent Strategic Initiatives: ARKO’s hallmark is rapid acquisition-driven expansion:

The company has completed 25 acquisitions since 2013, with 5 acquisitions just between Q3 2022 and Q4 2023. These five deals added approximately 720 store locations (either operated or supplied) to ARKO’s network – a huge expansion. For example, in 2022-2023 ARKO acquired chains like Pride Convenience Holdings (31 stores in Massachusetts), Transit Energy Group (a large acquisition of 135 stores and 190 supply sites in the Southeast), Quarles Petroleum’s fleet fueling business (121 fuel sites and 46 tankwagon trucks focusing on commercial fleet fuel), and several smaller clusters of stores across different states. Each acquisition is integrated and contributes to growth.

ARKO’s most ambitious attempt was its bid to acquire TravelCenters of America (TA) in early 2023. TA is a major truck stop chain. ARKO made an unsolicited $1.4 billion bid (at $92/share) to buy TA, competing against an accepted offer from BP. Ultimately, TA’s board rejected ARKO’s bid as not superior (citing financing and closing risks), and BP acquired TA. This episode shows ARKO’s aggressive growth mindset – it was willing to take a big swing to nearly double its size overnight. Missing out on TA means ARKO continues to focus on smaller deals, but management has indicated they remain on the lookout for transformative opportunities.

Organic initiatives: Alongside acquisitions, ARKO has been investing in organic growth initiatives at its stores. Key ones:

Loyalty Program Expansion: As noted, fas REWARDS membership surged, and they ran special promotions ($10 sign-up bonus) to build the base. Loyalty data helps ARKO tailor offers and boost fuel gallons (loyal members often buy more fuel and merchandise).

Foodservice Upgrade: Hiring a foodservice head and scaling food offerings (e.g., adding quick-serve restaurant concepts or proprietary food in stores that previously lacked them) is aimed at capturing the higher margins and customer traffic from food. This also helps future-proof against fuel declines (since food is fuel-agnostic revenue).

Store Remodels: ARKO typically remodels or refreshes many acquired stores to improve layout and product mix. Modernizing stores can drive sales lifts.

Cost Synergies: ARKO prides itself on capturing synergies from acquisitions. They consolidate back-office systems, negotiate better vendor terms with greater scale, and optimize supply logistics. For instance, in acquisitions closed last year, ARKO immediately worked on adding its merchandising assortment and improving those stores’ sales in core categories. They have mentioned capturing synergies and improving EBITDA of acquired stores significantly within the first year or two post-acquisition.

One area ARKO will need to watch is its debt and leverage – all those acquisitions and sale-leasebacks mean ARKO has significant lease obligations and debt service. However, they seem confident given the large liquidity they still have and the cash flows from the expanded base.

🤼 Competitor Strategy Comparison – Current Tactics and Differences

The U.S. fuel distribution and marketing players above, while operating in the same broad industry, have distinct strategic focuses and tactics. We can compare them across a few dimensions: degree of integration, growth strategy (acquisition vs organic), customer focus (wholesale B2B vs retail B2C), and approach to market trends.

Integration & Scope of Operations:

Sunoco and Global Partners have a more integrated infrastructure-based strategy. Sunoco, especially after the NuStar acquisition, owns extensive pipelines and terminals in addition to distributing fuel to ~10k locations. It is primarily wholesale-focused (supplying dealers, commercial customers, etc.) and does not emphasize operating retail stores (it lets dealers run Sunoco-branded stations under long contracts). Global Partners straddles wholesale and retail – it owns terminals, does wholesale supply, and also runs a sizable c-store network (with ~400 company-op stores). Global’s integration is “vertical” – from terminal to gas pump – allowing it to earn margin at multiple points and control supply logistics internally.

CrossAmerica and ARKO are less about owning big infrastructure and more about downstream retail assets. CrossAmerica is essentially a distributor/landlord hybrid: it supplies fuel and owns station real estate, but often lets others operate the stores (though shifting more to operating itself). It doesn’t own pipelines or refineries. ARKO is heavily focused on operating convenience stores and capturing the full retail margin; it relies on others’ infrastructure for fuel supply (it has supply contracts with refiners and wholesalers for its stations, and some short-term storage, but not an integrated midstream system).

World Kinect is the most asset-light and broadest in product scope. It integrates primarily through information and contracts rather than physical assets – its global platform connects suppliers to customers. WKC doesn’t operate stores or own pipelines; it’s a service provider that coordinates across the chain. It’s integrated in the sense of offering a full menu of energy solutions (fuel, power, sustainability), but not via owned physical assets.

Wholesale vs Retail Focus:

Wholesale-centric: Sunoco (majority of gross profit from wholesale fuel distribution with fixed fees, plus some terminal fees), World Kinect (almost entirely wholesale/B2B), CrossAmerica historically (though shifting, it still gets a large chunk of EBITDA from wholesale supply margins and rents).

Retail-centric: ARKO (majority of gross profit from fuel and merchandise at company-operated stores), Murphy USA and Casey’s (not detailed above, but both are classic retail-focused fuel marketers). Global Partners is roughly balanced but has increasingly leaned retail (its GDSO segment contributed more than wholesale in recent years).

The wholesale-oriented firms (SUN, WKC, CAPL) generally have thinner per-unit margins but more volume and often more stable contract-driven income. The retail-oriented (ARKO, and GLP’s GDSO part) have higher per-unit margins and more diversification (merchandise sales) but are more exposed to consumer trends and local competition.

Growth Strategies:

Acquisition-Driven Growth: ARKO is the poster child – it has grown primarily via acquiring dozens of companies (20+ acquisitions since 2013). It explicitly pursues consolidation of c-stores. Global Partners also has grown significantly by acquisition (terminals, store chains, JVs) – 2023’s Motiva and Exxon JV deals were transformational. CrossAmerica has done a steady stream of smaller acquisitions (59 Applegreen stores announced 2024, 106 stores from 7-Eleven in 2021, fuel contracts in 2022). Sunoco has been more selective but did a big one with NuStar and before that purchased some transmix and retail assets. World Kinect’s growth historically came via acquisitions too (in the 2000s they bought many regional fuel distributors globally), but lately WKC’s focus is internal efficiency and new product lines rather than big M&A. So, all these companies have used M&A, but ARKO and GLP are particularly acquisition-focused as core strategy, whereas Sunoco did one large strategic deal and otherwise grows moderately, and WKC is targeting organic improvements.

Organic and Operational Growth: Sunoco emphasizes organic growth of distributable cash flow – it has managed to grow DCF per unit 8 years straight by enhancing margins, cutting costs, and small bolt-ons. Sun’s stable contract with 7-Eleven locked in a baseline, and it optimizes supply chain (buying in bulk, blending, etc.) to eke out extra margin. World Kinect’s strategy is very much about organic margin expansion – driving efficiencies, new services, and upselling renewable solutions, with relatively flat volume expectations. CrossAmerica’s organic growth is limited (its same-store volumes were down slightly), so it relies on acquisitions and site conversions to boost earnings (e.g., turning leased sites into higher-margin company ops). ARKO, beyond acquisitions, is pushing organic growth via loyalty and foodservice initiatives – in 2023 it saw same-store merchandise sales tick up +0.4% and merchandise margin expand 140 bps, showing some success. GLP has some organic initiatives too (like converting commission sites to company-op for better margin, and expanding prepared food in Alltown Fresh stores) but the big needle movers were acquisitions.

Strategic Initiatives & Differentiators:

Sunoco: Very disciplined, margin-per-gallon focused model. Its differentiation is the Sunoco brand (well-known, leveraged via long contracts) and now a large logistics network that few independent distributors have. Tactically, Sun has executed well on integration (NuStar done within 6 months, beating synergy targets). It’s also differentiated by being an MLP that consistently grows distributions – indicating strong cost control and prudent capital allocation (only doing accretive deals). Sun’s strategy is steady, not chasing retail or consumer-facing diversification – it’s sticking to “pipes and pumps” distribution and doing it at scale.

World Kinect: Differentiates by global reach and multi-fuel offerings. It’s the only one of these that can fuel a jet in Asia, bunker a ship in Europe, and deliver gas to a station in Florida all in one day. Its strategy to pivot to sustainability could carve a new niche (helping clients with ESG goals). Execution-wise, WKC has had some stumbles historically (e.g. past credit losses in marine, etc.), but currently it’s executing a leadership and branding refresh to reinvigorate growth. If it hits its 2026 targets (30% op margin, $500M EBITDA), that would mark a successful execution of its efficiency strategy.

Global Partners: Has shown bold strategic moves, using JVs and long-term contracts to expand inorganically while managing risk (the 25-year Motiva contract is a masterstroke to ensure stable cash from the new terminals). GLP’s execution has been strong lately – closing big deals and integrating them (terminals integration underway, JV stores to be operated by GLP’s proven retail team). GLP is tactically converting some sites to company-run to capture margin, and also did something innovative by monetizing part of its retail via sale to an MLP: in 2022, GLP sold half its retail propane business to an MLP to focus on core gasoline assets (not detailed above). That shows savvy portfolio management. GLP’s challenge is to digest the rapid expansion (a lot of new assets in a short time) – so far, market reaction is positive (stock up on earnings).

CrossAmerica: Its strategy is more defensive and partnership-oriented. It often acts in concert with big players (previously CST/Valero, then Couche-Tard). CAPL’s focus recently is on tweaking its portfolio – a bit of store growth, a bit of trimming. It’s a comparatively conservative executor, ensuring it can maintain its high distribution. CAPL did execute those asset exchanges with Couche successfully by 2020, and more recently executed smaller acquisitions smoothly (the 2021 and 2022 deals). One notable tactic: CAPL leverages relationships – e.g., buying Applegreen stores likely came because Applegreen wanted to exit the U.S., and CAPL’s known presence made it a natural buyer for a scattered batch of stores that bigger players might not want. The downside is CAPL hasn’t shown big organic growth or margin expansion – its 2024 earnings were down. Execution on improving the newly acquired stores (Applegreen) and trimming fat will be key to change its trajectory.

ARKO: Highly aggressive and opportunistic. Its strategy is basically “buy, integrate, repeat,” with a side of enhancing the business model (loyalty, food, private label, etc.). ARKO’s execution capabilities are quite impressive in M&A – 5 acquisitions in a span of a year is a lot, yet their EBITDA held strong and they claim synergies are being realizedarkocorp.com. ARKO was bold enough to challenge BP for TA, which shows confidence. Tactically, ARKO is excellent at financing its growth – the Oak Street sale-leaseback program has given it huge firepower ($2B liquidity)arkocorp.com without diluting shareholders much. The flip side: sale-leasebacks increase rent expenses, which ARKO must cover with operations; so far it has managed to keep profitability despite higher fixed costs. ARKO’s internal initiatives (loyalty, etc.) show it’s not just coasting on acquisitions – they are trying to modernize the chain and drive organic sales. Over the last two years, ARKO’s fuel margins and merchandise margins have been high relative to industry, indicating strong execution in pricing strategy and category management.

📈 Historical and Forecast Growth Performance

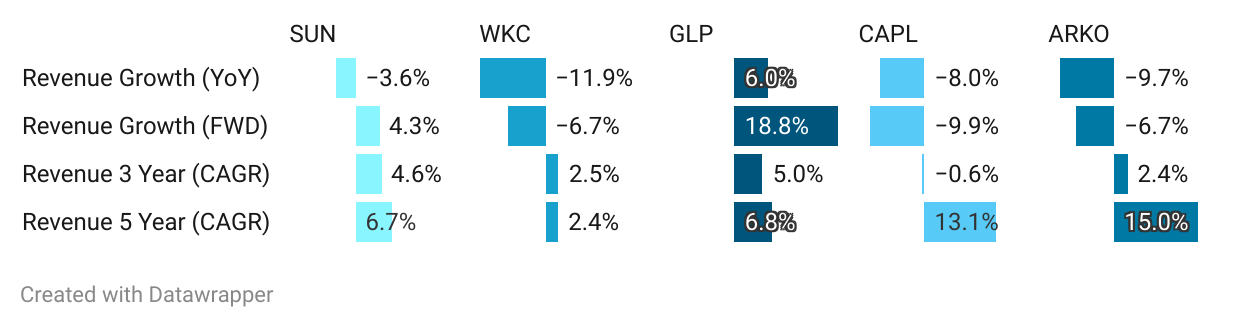

Five-Year Revenue CAGR: The standouts were ARKO and CrossAmerica, with ARKO at ~14.98% CAGR and CAPL at ~13.1% CAGR over five years (impressive double-digit annualized growth). These far outpaced Sunoco (~6.7%) and Global (~6.76%), while World Kinect trailed at only ~2.38% CAGR. ARKO’s nearly 15% CAGR reflects its aggressive acquisition strategy – it has essentially grown revenues by ~double over 5 years via numerous acquisitions. CrossAmerica’s ~13% is interesting: much of that likely came from the big asset exchanges and acquisitions around 2018–2021 (CST/Circle K and 7-Eleven deals). However, note that CAPL’s 3-year CAGR was slightly negative (-0.61%), implying that in the more recent 3-year window it didn’t grow (due to divestitures and lower fuel prices). ARKO’s 3-year CAGR was only ~2.4%, suggesting that aside from one big jump when ARKO went public and acquired Empire in 2020, its revenue growth stalled a bit in 2021–2023 (because fuel prices and volumes fluctuated). Global and Sun each had mid-single-digit 5-year CAGRs (~6-7%), indicating steady growth – likely partly volume, partly fuel price inflation – nothing spectacular but solid given the pandemic disruption in that period. World Kinect’s 5-year growth of ~2.4% is the lowest – essentially WKC’s revenues barely grew, meaning volumes were flat/down and any growth was mostly from price changes. Indeed, WKC has seen a stagnant top-line due to loss of some large contracts in mid-2010s and then pandemic impacts; it only started recovering in 2021–2022 but then 2023 saw lower fuel prices cut revenue again.

Most Recent Year (2024) YoY Growth: The data showed revenue growth YoY as: Global +6.04% (the only positive among the five), Sun -3.59%, CAPL -7.98%, ARKO -9.67%, WKC -11.93%. Global Partners was the only one to grow revenue in the latest year due to acquisitions. The others had revenue declines – a big factor is that fuel prices dropped in 2024 from 2023’s highs, which directly lowers revenue (even if gallons sold were flat or slightly down).

Forward Growth Expectations: Global Partners is expected +18.77% – by far the highest, whereas WKC is -6.69%, CAPL -9.86%, ARKO -6.73%, and Sun +4.27%. This suggests that Global Partners is projected to be a growth leader in the near future, likely because analysts factor in a full year of new JV stores and the Motiva terminals contribution (even though terminal fees don’t boost “revenue” as much, the fuel throughput might). A nearly 19% forward growth indicates significant expansion – GLP will have more volume to sell (especially with the Houston stores now in its fold, and possibly it will have incremental wholesale opportunities via the new terminals). In contrast, CAPL, ARKO, WKC are all expected to see revenue declines next year. Why? Possibly because fuel prices in 2025 might be assumed slightly lower or flat, and these companies might not have major acquisitions closing to boost sales.

📊 Industry Trends and Growth Drivers

The fuel distribution and marketing industry is experiencing a number of important trends and facing both macro-level and micro-level drivers of growth (or decline). Below are several key trends and drivers impacting U.S. fuel distributors and marketers:

1. Energy Transition and EV Adoption:

Perhaps the most profound long-term trend is the shift towards electrification of transport and lower-carbon fuels. The rise of electric vehicles (EVs) poses a gradual but existential challenge to gasoline demand. EV market share in the U.S. is growing (around 6% of new car sales in 2022, increasing in 2023), and many states (like California, New York) have set targets to ban new gasoline car sales by 2035, which over time will reduce fuel consumption. For the fuel marketing industry, this is a crucial trend: flat or declining gasoline volume growth is expected over the next decade nationally (with some regional variation). However, the pace of EV penetration is uncertain. Interesting to note, globally there have been some hiccups – for instance, in Europe EV sales actually fell slightly in 2024 when subsidies were cut. This suggests EV growth can be policy-sensitive. In the U.S., the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act introduced EV purchase tax credits which boost adoption, but if incentives wane or if infrastructure lags, EV growth might slow. Nonetheless, the consensus is gasoline demand will gradually erode in mature markets.

For fuel distributors, EVs are both a threat and an opportunity:

Threat: Less gasoline/diesel demand means fewer gallons to distribute, threatening volume throughput and fuel revenues. Particularly for companies highly levered to gasoline retail (like ARKO, Casey’s) or diesel wholesale (like some of WKC’s fleet fuel business).

Opportunity: Many fuel marketers are pivoting to offer EV charging services at their locations. Gas stations are logical sites for EV fast chargers (with their infrastructure and amenities for drivers waiting). Some companies have started installing chargers – e.g., ARKO piloted EV chargers at a few stores; Global Partners has discussed EV charging (especially at its Alltown Fresh upscale stores) and even World Kinect could leverage its commercial fleet relationships to provide energy services for EV fleets. However, EV charging has a very different business model (electricity is typically lower-margin per “fill” than gasoline, and dwell times are longer which changes the convenience store dynamic). Still, companies see that offering EV charging can keep them relevant. Large firms like Pilot/Flying J (private, now partly owned by Berkshire Hathaway) are rolling out charging stations in partnership with car makers.

Mitigation strategies: Fuel distributors are diversifying product slate – Renewable diesel and Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) are drop-in fuels that can reduce carbon without needing EVs, and many distributors (GLP, Sun, WKC) are handling these where possible (renewable diesel especially for trucks in California). Biofuels blending (ethanol, biodiesel) is already standard, and could increase with policy. Also, some companies are moving into adjacent energy: World Kinect now sells electricity and natural gas retail contracts (anticipating an electrified future), and has ventures in solar installation (small scale), etc. So, the trend is forcing distributors to evolve into broader “energy providers” instead of just petroleum sellers.

2. Regulatory and Policy Environment:

Regulation significantly influences this industry:

Emissions and Fuel Standards: Federal and state policies on emissions can reduce fossil fuel use. The Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) requires blending biofuels (ethanol, biodiesel) – fuel distributors must blend or buy credits (RINs). This can be a cost but also an opportunity (some distributors generate revenue by blending ethanol when economics favor it). Low Carbon Fuel Standards (LCFS) like California’s are spreading – some Northeast states are considering similar programs. LCFS programs encourage use of renewable diesel, renewable natural gas, etc., which distributors may handle.

Environmental Compliance Costs: Fuel marketers have compliance costs for things like vapor recovery, underground storage tank upgrades, etc. These can drive consolidation (small operators sell out because they can’t afford compliance upgrades – benefiting larger players like ARKO or GLP who can). Recent example: many stations had to upgrade fuel dispensers for EMV chip card readers by 2021 – some small ones closed or sold, which helped consolidate volumes to the remaining players.

Labor and Wage Laws: Many c-store chains are large employers. Rising minimum wages (several states and localities now $15+) and tight labor markets drive up labor costs at gas station convenience stores. This squeezes margins if not offset by price increases or productivity improvements. Companies like Casey’s and ARKO have cited higher wage expenses impacting results, prompting them to invest in automation (self-checkouts, etc.) and optimize staffing.

In summary, regulation is pushing towards cleaner fuels and imposing costs that favor larger, well-capitalized firms – a driver of consolidation. It also creates new markets (renewables, credits) that savvy companies can exploit.

3. Convenience Retail Evolution and Diversification:

As fuel margins can be volatile and long-term volumes face headwinds, convenience store retailing has become increasingly important for profitability. Industry players are doubling down on making their locations destinations for more than just fuel:

Foodservice and Private Brands: C-store chains are investing in fresh food (e.g., made-to-order sandwiches, pizza, gourmet coffee). This not only yields higher margins (foodservice gross margins can be 50-60%) but also drives customer loyalty and can bring new customer segments. Casey’s General Stores is an exemplar – its pizza program is famous and highly profitable. ARKO hiring a foodservice VP, Global’s Alltown Fresh stores offering upscale organic food, etc., all signal this trend. Private label products (snacks, drinks with the store’s brand) also give higher margin and differentiate from gas station to gas station.

Loyalty Programs and Digital Engagement: C-store fuel marketers now widely use loyalty apps (e.g., BPme, Casey’s Rewards, Shell Fuel Rewards, ARKO’s fas Rewards) to retain customers and personalize promotions. Loyalty can increase visit frequency and also allow targeted marketing of in-store items. The data collected is valuable to refine store inventory and promotions. ARKO’s 50% increase in loyalty membership in a year underscores how crucial this is to strategy.

Store Format and Experience: There’s a trend towards larger, nicer convenience stores with more amenities (seating, Wi-Fi, broader product selection) – basically blurring the line with quick-serve restaurants or mini-truck stops. Companies see that as fuel demand eventually ebbs, making the store a desirable stop for food, coffee, or other services is key. For example, some urban convenience stores might even de-emphasize fuel (7-Eleven has some no-fuel small format stores now) focusing on grab-and-go food.

E-commerce and Delivery: Some convenience retailers partner with delivery apps (DoorDash, UberEats) to deliver convenience items or prepared food, leveraging the store as a “mini-fulfillment center”. Casey’s and 7-Eleven do this. It’s a micro driver that can grow merchandise sales beyond the forecourt traffic.

Adjacent Services: To increase reasons to visit, stations are adding services like car washes (a profitable add-on using the same real estate), ATMs, even lockers for package pickup (Amazon lockers, etc.). Car washes in particular are a nice margin business that many fuel marketers expand into – e.g., ARKO, Global, Sun all operate car washes at some sites. Some large chains (e.g., Shell via third parties) are exploring adding EV charging as an ancillary service – attracting EV drivers who might then use the store while they charge.

Fuel Pricing Strategies: On the fuel side, retailers are employing more sophisticated pricing to maximize margin. Many use algorithms that adjust prices in real-time based on local competition and inventory cost (price optimization software).

4. Fuel Supply & Pricing Dynamics:

Fuel distributors are exposed to the swings of oil and refined product markets:

Price Volatility: Sharp changes in fuel prices can affect distributors in complex ways. In general, falling wholesale prices tend to expand retail margins (because retailers lower pump prices more slowly than wholesale drops, capturing windfalls), whereas rising prices can squeeze margins (retailers lag in raising prices, or fear losing sales, so margin per gallon dips). We saw this in 2022: fuel prices soared, but many distributors and retailers had record margins (contrary to expectation) because volatility itself creates opportunities (wholesalers and traders can profit from timing, and retail margins widened once prices stabilized at high level). In 2023, prices fell and indeed many reported margins remained healthy or even improved. For distributors like Sunoco, stable margins were protected by fixed contracts. But those that rely on spot purchasing can benefit in contango markets (buy cheap, store, sell later).

Refining Capacity and Supply Constraints: Regional supply issues (refinery outages, pipeline problems) can create localized opportunities for fuel distributors who have flexibility. E.g., if a refinery in the Northeast goes down, wholesale spot prices jump – those with storage (GLP) can supply the short market at higher margins. Conversely, oversupply can compress margins.

Seasonal Demand Shifts: There are seasonal volume patterns (summer driving season, winter heating oil demand in Northeast) that impact fuel marketers. Companies manage inventory and contracts to prepare for these. Renewable fuels also have seasonal patterns (ethanol blending increases in summer due to RVP regulations changes).

Commercial vs Retail Demand: On-road diesel demand is tied to freight and economic activity. There’s currently a trend with e-commerce and freight volumes: a slowdown in 2023 freight reduced diesel demand a bit, hurting those like WKC with heavy commercial exposure. If the economy picks up or infrastructure spending (trucks, construction) increases, diesel demand (and margins) could strengthen. Gasoline demand is tied to commuter patterns – the work-from-home shift from COVID has somewhat reduced gasoline demand permanently (less daily commuting), a micro trend that fuel marketers have noted (gas demand still hasn’t returned fully to 2019 levels). Distributors adapt by focusing more on interstate travel centers or areas with growth (Sunoco, for instance, expanded in Texas where driving is still increasing).

5. Renewable and Alternative Fuels Uptake:

Beyond EVs (covered in energy transition), the push for renewable fuels is a significant trend:

Renewable Diesel (RD): RD is a direct diesel substitute made from fats/oils, chemically identical to petroleum diesel. It’s booming particularly in California due to LCFS and tax credits. Many truck fleets and distributors have begun carrying RD where available. Several refiners (Marathon, Phillips 66) converted refineries to RD production. Fuel distributors that operate in those markets (e.g., Global in the West Coast via recently acquired terminals, or Parkland in west, though Parkland is Canadian) can distribute RD.

Ethanol and Blends: Ethanol has been 10% of gasoline for years (E10). Now E15 (15% ethanol) is slowly expanding – the EPA has been allowing summer E15 sales recently to help lower pump prices. More retailers are adding E15 (often marketed as Unleaded 88) as it can be a couple cents cheaper and has subsidy in some states. Fuel marketers benefit by selling more ethanol (cheaper wholesale). If E15 becomes more standard, that slightly increases fuel volume (ethanol volume) to distribute. On the flip side, fuel distributors have to ensure infrastructure compatibility (most new stations can handle E15, older ones need minor upgrades).

Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF): Still in infancy, but companies like World Kinect are at the forefront of supplying SAF to airlines. SAF uptake is small due to high cost and limited supply, but with the aviation industry pushing net-zero goals, SAF could be a growth area. WKC has a natural advantage here given its aviation fueling dominance; if SAF production scales (with government incentives in IRA for SAF credits), WKC could grow by supplying it. Others like Avfuel (private) also active. Not directly relevant for Sun/GLP/CAPL as they don’t serve aviation, but for WKC it’s a micro driver.

Hydrogen Fuel: For heavy-duty transport, hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are a possible alternative (especially in trucking or fleet). While still very niche, some truck stop operators (e.g., TravelCenters before being bought by BP, and Pilot with Nikola partnership) have explored installing hydrogen refueling. It’s not mainstream yet, but distributors are keeping an eye. If hydrogen trucks catch on (mid to late 2030s possibly), fuel marketers might add hydrogen fueling at select locations. Not a near-term driver, but part of future-proofing strategy for some (e.g., Shell is pilot testing hydrogen stations in California).

6. Consolidation and M&A Continues:

The industry remains fragmented, especially on the retail end – there are still thousands of single-station or small-chain owners. Meanwhile, the economics and complexity (environmental compliance, technology investment, thin margins) favor scale. So consolidation is an ongoing trend. As companies scale, efficiencies improve, which can further drive smaller players out – a virtuous cycle for consolidators. Larger distributors have better terms with suppliers (bulk buying discounts) and can spread fixed costs (IT, compliance) over more gallons, giving them a margin edge. This is why Sunoco’s COO mentioned “marginal less-efficient operators” needing higher margins to survive, benefiting Sun. So, consolidation is both a trend and a driver: it’s happening because of thin margins, and it itself drives margin expansion for those consolidators.

7. Technology and Operations Improvements:

On a micro level, technology adoption is driving changes:

Automation & Digitalization: Fuel distributors are using software to optimize routing of fuel trucks (saving fuel and driver hours), forecast demand at stations to schedule deliveries just-in-time (prevent runouts while minimizing inventory carrying). They’re also implementing enterprise systems to manage pricing, credit, and logistics more efficiently. World Kinect, for example, emphasizes using data to drive efficiency (they even mention AI-driven solutions for renewable energy and logistics). Back-office automation can reduce overhead costs, which is crucial for margins.

Customer-facing tech: Mobile apps for payment (e.g., Pay at pump via app), self-checkout kiosks in stores, and even autonomous checkout tech (Amazon’s JustWalkOut in some c-stores) are gradually coming. These improve customer experience and potentially reduce labor costs.

Fleet cards and payment: Many distributors run fuel card programs for fleets (like WKC’s Multi Service Aero card for aviation, or fleet fueling networks such as CFN that World Kinect offers). The transition to chip cards (EMV) at pumps by 2021 was a tech challenge – most majors met it, but it weeded out some weaker sites. Now, contactless and mobile payments are rising – fuel marketers are adopting these to enhance loyalty (tie payment to loyalty for seamless rewards).

Security and Cyber: As systems digitize, cybersecurity becomes a concern – protecting POS and fuel inventory systems from hacks (there have been instances of attempted hacks on fuel distribution networks). Larger, tech-savvy firms can better invest in cyber defenses than small ones, another consolidator advantage.

🎯 Key Success Factors and Profitability Drivers

Despite thin margins and an evolving landscape, many companies in this sector thrive. The key success factors – the critical things a company must do well – and the underlying drivers of profitability include:

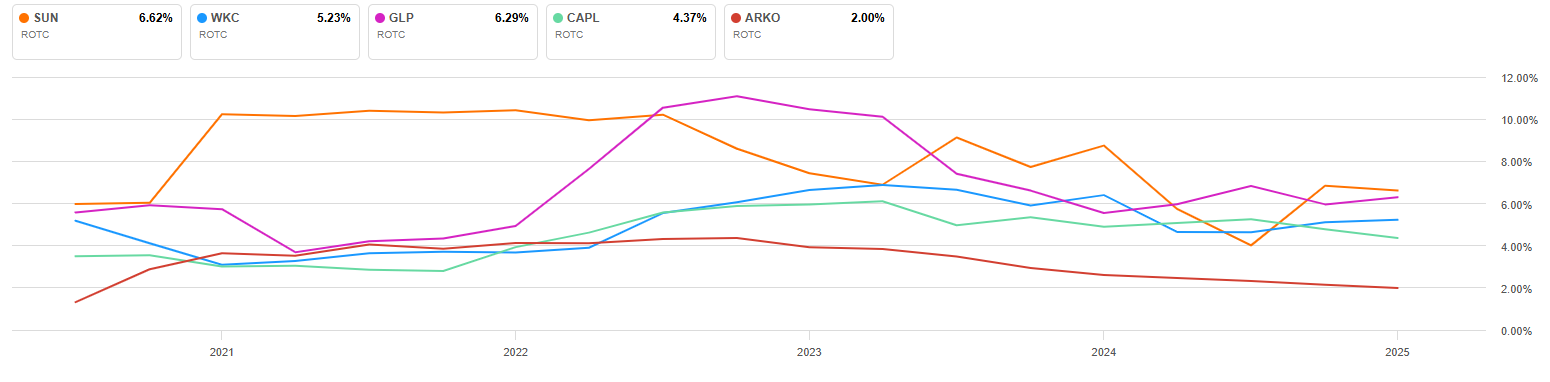

Scale and Volume Leverage: Economies of scale are crucial. Distributing billions of gallons allows a company to negotiate better fuel procurement terms (bulk purchasing power with refiners), reduce per-unit transportation cost, and spread fixed overhead over more volume. High volume also means even a tiny per-gallon margin yields significant gross profit. Sunoco, for example, leverages being the largest independent distributor (9+ billion gallons) to buy fuel at lower cost and use its vast logistics network efficiently. Scale also matters on the retail side – big chains get better vendor pricing for merchandise and can advertise more effectively. Scale is why consolidation yields synergies: ARKO noted that adding stores increases its purchasing efficiency and helps reduce cost of goods sold for merchandise.

Operational Efficiency and Cost Control: Given low gross margins, controlling operating expenses is paramount. This includes logistics optimization (scheduling deliveries to minimize miles and avoid empty backhauls), maintenance of equipment to prevent costly downtime, and tight management of labor at retail stores (avoiding overstaffing, reducing turnover). Companies employing advanced logistics software (routing, inventory management at stations) can cut fuel delivery costs. On the retail side, efficient store operations (e.g., training staff to multitask, using self-checkouts) improve profit. Successful companies tend to have lower operating cost per gallon or per store than peers. For instance, Sunoco touts that as one of the most efficient operators, it benefits when margins tighten because it can still profit where higher-cost rivals struggle.

Fuel Margin Management and Procurement Strategy: Profitable fuel marketers excel at managing fuel pricing and margins. This involves:

Supply sourcing: Diversifying supply sources and using spot vs contract purchasing shrewdly. Companies with terminals can source fuel cargoes opportunistically. Hedging price risk when needed to protect inventory value. For distributors, maintaining a balanced inventory (not over-buying at high prices or running out at low prices) is key.

Pricing strategy: Using data to set retail prices that optimize margin without sacrificing too much volume. Many successful retailers adjust prices multiple times a day to track market moves and competitor actions. They also use zone pricing (different prices at stations in different areas based on local demand elasticity).

Fixed fee contracts: As seen with Sunoco’s 7-Eleven deal, locking in fixed per-gallon margins on core volume provides a stable base of profitability. This model can be a success factor because it shields from volatility – Sun can then take on some spot market exposure with less risk to overall results.

Managing breakeven: Understanding one’s cost structure and the “floor” margin needed. Efficient players know they can still earn money at lower margins than mom-and-pop shops, so they might let price wars go to a certain level where small players drop out, then recoup margin later.

Strategic Location and Asset Quality: For retailers, location is king – high-traffic, easily accessible sites lead to higher fuel volumes and in-store sales. Companies that have a network of stations on busy intersections, near highways, or in growing neighborhoods will outperform those with poorly located sites. Similarly for distributors, having fuel terminals in strategic locations (e.g., near demand centers or pipeline connections) is a success factor – it allows quick response to supply issues and lowers transport cost to customers. Global Partners acquiring terminals in seven new states significantly boosts its strategic coverage, for example. Also, maintaining assets (tanks, pumps) in good condition avoids downtimes that can lose sales and ensures safety (avoiding costly environmental incidents).

Brand and Customer Loyalty: A strong brand can drive customer preference and pricing power. Sunoco’s nationally recognized brand attracts both station owners (who want a known brand to draw customers) and consumers (who might trust Sunoco fuel quality and sponsorships like NASCAR). Having a proprietary brand program (like Sunoco, or even World Kinect’s own small brands Amstar/XTR for independents) is an advantage. On the retail side, brand extends to the store experience – companies like Casey’s or Wawa have very loyal followings for their food and service, which keeps customers coming even if a competitor across the street is a couple cents cheaper on gas. Loyalty programs reinforce this, as discussed: they lock in repeat business and provide data to tailor offerings. Firms that foster loyalty can generate more visits and upsell more effectively, boosting profitability.

Diversification of Revenue Streams: The most profitable fuel marketers aren’t reliant solely on selling gasoline at a margin. They diversify into:

Convenience store merchandise sales: high-margin and less volatile than fuel. For example, selling coffee and snacks can yield 40%+ margins vs single-digit fuel margins. Companies that have robust convenience retail (ARKO, Casey’s, Couche-Tard) can weather fuel margin swings since the inside sales provide a stable profit base.

Foodservice: As noted, prepared food and quick-serve offerings yield strong margins and build store traffic.

Services: Car wash (often membership-based unlimited wash programs), ATM fees, lottery (lottery has slim margin but draws foot traffic that buys other stuff). Some sell propane cylinders, offer money order services, etc. Every extra service is an additional profit line.

Fuel variety: selling premium fuels, diesel, DEF (diesel exhaust fluid for trucks), etc. Premium grades typically have higher cents-per-gallon margins than regular unleaded. Truck stops selling bulk DEF or offering amenities for truckers earn extra.

B2B sales: Some companies serve commercial accounts (fuel cards for fleets, bulk deliveries). This can diversify away from purely consumer fuel sales. WKC is an example – it serves marine and aviation aside from road fuels, spreading its bets.

Alternative fuels & energy: Over time, offering EV charging (where you can earn per kWh fees, or attract customers to store while charging), or participating in renewable credits markets (some distributors generate revenue selling RIN credits if they blend more biofuel than obligated) contributes to income.

A diversified revenue mix means a company isn’t over-exposed to one segment’s downturn. For instance, in early 2020, gas sales tanked but convenience store grocery sales jumped as people stocked up locally – those with strong c-store operations mitigated losses from fuel.

Adaptability and Strategic Foresight: The industry is changing (EVs, regulations, consumer habits). Companies that anticipate and adapt have an edge. For example, developing EV charging strategies now, experimenting with new store formats, or partnering with tech companies for delivery can position a fuel marketer for future success. World Kinect’s pivot to an “energy management” approach is an example of attempting strategic foresight (diversifying before core business declines). This is somewhat intangible but critical – resting on old laurels (just selling gas like it’s 1990) could be fatal long-term. The companies in leadership tend to be those proactively evolving – e.g., Couche-Tard (Circle K) is testing EV charging stations with waiting lounges in Norway, Casey’s is leveraging its distribution fleet to potentially deliver to smaller stores, etc. Innovation becomes a success factor as new challenges arise.

💼 Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

Analyzing the competitive environment through Porter’s Five Forces provides insight into the pressures fuel distributors and marketers face in the U.S.:

1. Rivalry Among Existing Competitors – High

The fuel distribution and marketing industry is highly competitive and mature. There are many players ranging from global integrated oil companies to regional jobbers to hypermarket fuel stations, all vying for volumes and customers.

Wholesale Level: Distributors compete on price per gallon, reliability, and service to win supply contracts for gas stations or commercial accounts. Margins are razor-thin, and losing a big account (like a chain of stations) to a competitor willing to take a slightly lower margin is a constant threat. Companies like Sunoco, Global, and World Kinect face competition from other wholesalers (e.g., Pilot Company in commercial fuel, regional family-owned distributors, and even the integrated refiners’ own marketing arms). Rivalry is intense especially in regions with surplus supply (e.g., Gulf Coast) where distributors undercut each other for volume.

Retail Level: The retail fuel market is characterized by frequent price wars. Gasoline is a commodity and consumers are price-sensitive (many will drive out of their way for 5¢/gal cheaper). Competitors include other branded stations, independent unbranded stations (which often price lower), and new formats like Costco, Sam’s Club, and other big-box retailers that use fuel as a loss leader. Hypermarkets have significant market share in U.S. gasoline sales and are fierce competitors, often with very low margins accepted because fuel drives their store traffic. This puts pressure on standalone gas stations to match prices or lose volume. In convenience retail, rivalry is also strong – many chains compete on food offerings, store cleanliness, loyalty perks, etc., to capture consumer wallet share. If one chain launches a new food item or loyalty discount, others quickly follow or counter, making differentiation challenging.

Consolidation Impact: With industry consolidation, the remaining players are larger and often go head-to-head in markets. For example, if Casey’s and Couche-Tard (Circle K) both operate in the same town, they closely watch each other’s pricing. Consolidation can sometimes reduce the number of competitors in a locale (less independent stations), potentially easing rivalry slightly, but overall the major chains then vigorously compete. In fuel distribution, consolidation means a few big distributors might dominate a region and still aggressively try to poach each other’s clients.

Low Switching Cost: Customers (both station owners at wholesale and drivers at retail) can switch easily. A station owner can change fuel supplier (often contracts are 3-7 years, but once up, they can switch brands or jobbers), and drivers can choose another station next fill-up without cost. This fluidity heightens rivalry – companies must constantly fight to retain accounts and consumers.

2. Threat of New Entrants – Moderate (overall); Varies by segment

Barriers to entry in fuel distribution/marketing are mixed:

Wholesale Distribution: On one hand, at a small scale, entry is relatively easy – anyone with some capital can become a fuel reseller or jobber (buy fuel from a terminal and deliver to local stations) on a limited basis. There are many small family-owned distributors. However, to achieve efficient scale and compete with established players on price, new entrants face hurdles:

Capital Requirements: Building or acquiring terminals, delivery trucks, and complying with environmental regulations requires significant investment. A new entrant likely needs to invest in fuel trucks, storage tanks, or have strong credit to secure supply from refiners. The industry also often requires providing financing or equipment to gas station customers as part of supply agreements – not easy for a newbie.

Regulatory Hurdles: Licenses to handle fuel, environmental permitting for storage, etc., add complexity. Established players have compliance systems in place.

Relationships and Contracts: The market in many regions is saturated with supply contracts. New entrants will find it hard to break in unless they severely undercut margins or take on risky customers. Large chains typically already have supply deals (with majors or big distributors). There’s some consolidation loyalty – e.g., a station carrying a major brand likely has a contract with that brand’s authorized distributor.

Brand and Trust: In wholesale, having a recognized brand (like Sunoco) can help win station accounts because station owners want a known fuel brand to attract drivers. A new independent distributor lacks brand cachet, unless they can license a major brand which usually requires proving capabilities.

Retail Gas Stations: Entry here means establishing new gas stations or convenience stores. Barriers include:

Site availability and cost: Good locations for new stations are harder to find (especially in cities or developed suburbs). Land and construction costs are high. Many local zoning laws now limit new fuel station developments for environmental or traffic reasons. In some places (e.g., parts of California), there’s even political resistance to new gas stations as policy shifts to EVs.

Scale for competitiveness: A one-off new station might struggle to compete against big chains on fuel price (they can’t buy fuel as cheaply) and on marketing. Most new entrants in retail are often franchisees of established brands or well-capitalized firms. Indeed, we see more exit of small independents than entry – many sell out to larger chains instead of building new.

Brand/franchise support: New gas station owners typically license a major oil brand or join a chain franchise (because independent fueling is tough without brand draw). That means a “new” station often piggybacks on an incumbent brand’s network, not truly an independent entrant.

However, threat of new formats: Non-traditional entrants like Tesla (with Superchargers) or EV-only charging chains, and big retailers adding fuel (like grocery chains installing gas pumps), can be considered new entrants to fueling market share. For example, Uber or Amazon might one day leverage networks for fleet fueling – this is speculative but tech entrants could alter future dynamics (though currently they partner with existing players or use fleet cards).

Overall, new entrants can and do pop up (e.g., new local c-store opens, new truck stop built along a highway), but the trend is more consolidation than fresh entrants. The market’s low margins and high efficiency of incumbents make it difficult for a newcomer to scale up profitably without significant capital and differentiation.

3. Bargaining Power of Suppliers – Moderate to High

In fuel distribution, the key suppliers are:

Refining companies and fuel producers (major oil companies like Exxon, Chevron, BP; large refiners like Marathon, Valero; regional refiners; and also fuel importers/traders). These suppliers provide the gasoline, diesel, etc., that distributors sell.

For convenience retail, suppliers include consumer goods manufacturers (Coke, Pepsi, candy companies, etc.), but typically their power is lower because c-stores are fragmented and have many alternative products to stock (Coke vs Pepsi, etc.). We’ll focus on fuel supply power.

The bargaining power of fuel suppliers can be significant:

Market concentration: While there are many refiners, in certain regions supply can be dominated by few players. For instance, on the West Coast, a handful of refiners supply most gasoline; in the Northeast, loss of local refineries means distributors rely on a few importers and Gulf Coast suppliers. If a distributor operates in a region with limited supply points, the refiners/terminals there can dictate terms (especially in shortages).

Integrated Majors and Brand Control: The major oil companies (ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, Chevron, etc.) not only supply fuel but also control the branding that many retail stations use. They often have franchise/exclusive supply agreements with distributors – e.g., a jobber authorized to carry Shell brand must buy from Shell’s supply network and adhere to Shell’s terms. This gives the supplier (Shell) power: they can set wholesale prices via formulas and the distributor has limited flexibility (they must pay the “dealer tank wagon” price Shell sets). If a distributor doesn’t like terms, they risk losing the brand. So, branded fuel suppliers exert considerable power on those carrying their flag.

Commodity nature and alternative sources: On the flip side, fuel is a commodity – if one refiner’s price is too high, a distributor can try to source from another or import if they have access. In major hubs (Gulf Coast, New York Harbor), fuel supply is fungible. Large distributors can shop around for the best deals, which reduces individual supplier power. For example, Sunoco can source unbranded fuel from dozens of terminals – no single refiner can overcharge them much without Sun switching supply. World Kinect, operating globally, can arbitrage between suppliers.

Short-term versus Long-term dynamics: In normal times when supply exceeds demand, suppliers have less power (they’re eager to sell, and distributors can negotiate better discounts or get incentives like prompt-pay discounts). But in tight market conditions (e.g., hurricanes knocking out refineries, or rapid demand rebound), suppliers gain power – they allocate limited fuel and can charge higher margins. Distributors then have to accept higher costs or risk empty racks.

Scale of buyer (distributor) matters: A large distributor like Sunoco (buying 8+ billion gallons) has more negotiating clout with refiners than a small jobber. Refiners want guaranteed offtake, so they may give volume discounts or better contract terms to big buyers (especially on unbranded fuel). Smaller distributors might pay more or get cut first in allocations during shortages, reflecting weaker bargaining position vis-à-vis suppliers.

Alternative fuel suppliers: Distributors could integrate upstream by importing fuel themselves if domestic refiners are too pricey – but that requires infrastructure (docks, storage). Global Partners, for instance, can import gasoline from Europe if East Coast refiners raise prices too high, thus limiting supplier power. Not all distributors can do that.